Crosses: Dutch Kills

Location: Long Island City, Queens [satellite map]

Carries: 1 freight track (Long Island Railroad)

Design: (former) swing bridge, now fixed into place

Date opened: 1893

The Dutch Kills Swing Bridge was built by the Long Island Railroad as part of its Montauk Branch in 1893. Located in the southern part of Long Island City, it crosses the Dutch Kills, a tributary of Newtown Creek.

Dutch Kills and the Growth of Long Island City

As discussed in the history of the Hunters Point Avenue Bridge, the land surrounding Dutch Kills (“kills” is “creek” in Dutch) was originally marshland. The area’s first European settlement was in 1642 by Richard Bruntall, who owned 100 acres of land on the eastern side of Dutch Kills where it meets Newtown Creek [1]. To the west lay an area purchased by minister Dominie Everardus Bogardus for use by the Dutch Reformed Church called Dominie’s Hoek (Hook). In 1664 it became part of the Town of Newtown and later was given to British sea captain George Hunter. It was renamed Hunters Point in 1825. Both Hunters Point and the area surrounding Dutch Kills remained quiet farmland and estates until the 1840s, when industry began to grow on Newtown Creek. The railroads arrived in the 1850s, and industrialization continued. In 1870, Astoria, Ravenswood, and Steinway incorporated with Hunters Point to form Long Island City. Both Newtown Creek and Dutch Kills were used heavily by factories and other businesses located on their banks necessitating the construction of a number of movable bridges.

The Railroads and Hunters Point

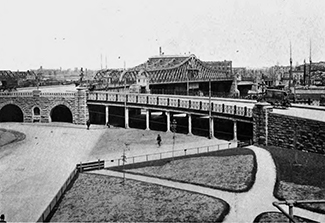

The Hunters Point area of Long Island City has a long history as a transportation hub. As New York City expanded, so did the need for commuting. Before bridges and tunnels connected Manhattan to Brooklyn, Queens, and New Jersey, passengers relied on ferries to cross the East and Hudson Rivers, often directly linking to railroads continuing to points further afield. In 1854, the Hunters Point Terminal was opened by the Flushing Railroad. It was the first railroad to operate in Long Island other than the Long Island Railroad (founded in 1834) and ran from the Hunters Point waterfront where Newtown Creek empties into the East River to Flushing, Queens. The ferry followed soon after the railroad: from 1858 until its closure in 1925, the Thirty-fourth Street Ferry crossed the East River between Manhattan’s east side and the Hunters Point Terminal. The Flushing Railroad was reorganized in 1859 as the New York and Flushing Railroad. Hunters Point continued to grow, and by 1873 two additional railroads had moved in: the Flushing, North Shore and Central Railroad and the South Side Railroad both constructed terminals. By 1884 all the railroads had been merged into the Long Island Railroad. Passengers could travel via the Lower Montauk Branch across the Dutch Kills to Penny Bridge (which provided access to Calvary Cemetery) and points further east.

C.C. Schneider’s Bridges

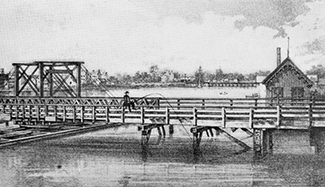

The first rail crossing of the Dutch Kills opened in 1854 along with the railroad; no information about it was found. The expanding Long Island Railroad replaced it with a two-track swing bridge in 1880. The bridge was designed by the German-born American civil engineer Charles Conrad (C.C.) Schneider. Schneider later wrote that the span opened, but with difficulty:

It occurred to the writer that a bridge which is to be used as a fixed span, but must be designed so it can be opened, should meet, in the first place, the conditions most desirable in a permanent structure, viz., when closed it should be practically a fixed span, resting on substantial supports, which, however, could be removed if it should become necessary to open the bridge. This, to the writer’s knowledge, was the first swing bridge where wedges were used as supports at the center. The arrangements for operating the wedges was very crude. [2]

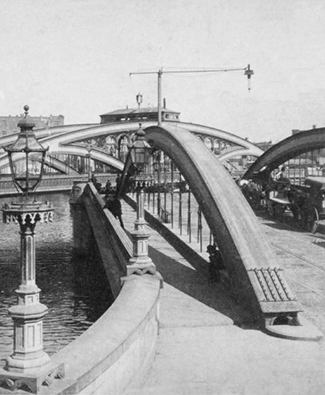

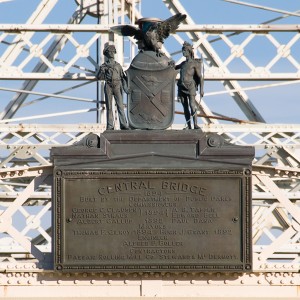

The wedge design for swing bridges never caught on, but Schneider continued to build bigger, more well-known bridges. In 1882, the Michigan Central Railroad asked him to submit a proposal for a bridge across the Niagara Gorge; his design for a two-track cantilever bridge was accepted and built the following year and came to be known as the Niagara Cantilever Bridge (it was replaced in 1924-5 by the Michigan Central Railway Bridge, of an arch design, which is abandoned but still standing). Also in 1883, he started his own civil engineering firm in New York City. In 1885 his design for an arch bridge across the Harlem River north of High Bridge was selected and opened in 1889 as the Washington Bridge. He partnered with the Pencoyd Iron Works in 1886. The company, founded in 1857 and located along the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania, had started out making wrought iron but by that time had become a major supplier of steel for bridge building. Schneider, using Pencoyd steel, designed and built bridges for various railroads, among them the Pennsylvania and the Chesapeake and Ohio. He was an early engineer on an East River bridge proposed by the Long Island Railroad in 1893. Construction on that bridge started in 1895 but quickly ended due to a lack of funds–later the Blackwell’s Island Bridge was built (now known as the Queensboro Bridge) across the same stretch of the East River.

Current Bridge

While not nearly as high-profile as the Blackwell’s Island Bridge, Schneider designed another bridge in 1893: a replacement for his 1880 span across the Dutch Kills. The channel for boats was widened and demand to use the waterway was up, so the new swing bridge was larger, longer, and carried three (rather than two) railroad tracks. It was of a more modern swing design and, while providing little clearance above the water, it was capable of opening far faster than its predecessor. As was the case with its predecessor, the rail line was in use by both freight and passenger trains. It was operated from a tower called DB Tower south of the tracks on the west side of Dutch Kills.

Wheelspur Yard

A train yard which came to be known as the Wheelspur Yard was located on the western side of the creek and took up much of the land south of the tracks. It included a turntable and was used to store passenger trains. The yards were enlarged northward in 1903-4. During another yard expansion in 1915, DB Tower it was demolished and replaced by a small building on the east side of the creek, known as DB Cabin; the Dutch Kills Swing Bridge is also referred to by this name.

The East River Tunnels

The Long Island Railroad, despite its heavy use, continually failed to be profitable and the Pennsylvania Railroad bought a controlling interest in it in 1900 and began subsidizing it. Penn Station opened in 1910, along with its East River Tunnels, which meant that LIRR passengers could travel from Manhattan to Queens and Long Island directly by rail. The PRR had built Sunnyside Yard (northeast of Wheelspur Yard) to store its trains and much rail activity in the area moved there. In 1917 the East River Connecting Railroad (which includes Hell Gate Bridge) opened, meaning that passengers could leave Penn Station for points in the Bronx and as far north as Boston. Shortly after the opening of Penn Station, a connection between the Lower Montauk Branch and Sunnyside Yard was created, called the Montauk Cut-off. A Scherzer Rolling Lift bridge was built just north of the Dutch Kills Swing Bridge and was operated from Cabin M on the east bank of Dutch Kills.

Decline

Penn Station and all the changes it brought added up to a steep decline in use for the Lower Montauk Branch. The Thirty-fourth Street Ferry suffered such a loss of ridership that it shut down operation in 1925. By 1930, Wheelspur Yard was seldom used, though it was resurrected during the 1939-40 World’s Fair in Flushing and was then used for train storage by the Pennsylvania Railroad. The rail industry in general suffered after World War II and the struggling PRR stopped subsidizing the LIRR. The Long Island Railroad went into receivership in 1949 and was then subsidized by the State of New York. By 1959, the Pennsylvania Railroad had ceased to use Wheelspur Yard, and much of it was sold off and its tracks removed. In 1966, the LIRR was taken over by the newly-created state-funded Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority (which changed its name to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 1968).

As use of the line decreased, tracks were removed; eventually only one track remained on the Dutch Kills Swing Bridge, but it was off-center. According to an account on LTV Squad, in the late 1980s an opening was attempted but failed because the bridge was unbalanced on its center pier. Emergency repairs were made and the single track was relocated to the center, but the bridge has remained in the closed position ever since. The New York and Atlantic Railway took over the LIRR’s freight operation in 1997 and continues to run freight trains over the route to this day. In 1998, LIRR trains stopped for the last time at five of the Lower Montauk’s stations: Penny Bridge, Haberman, Fresh Pond and Richmond Hill. Once-daily commuter service continued on the line out of Long Island City but had ended by 2013. The bridge is in a sorry state. Historical photos of it are hard to come by, but several images, such as those on Arrt’s Archives, from the 1950s and 1960s show it to have been painted black (many bridges were painted black during WWII). It has since been painted an off-white hue which has flaked off to the point where the bridge appears mottled: rust-brown overtaking lighter tones. The bridge’s northwest beam once bore a plaque that read “built by the Pencoyd Bridge & Construction Co / Pencoyd PA / 1893.” It is now broken and rusted, its lower half missing. (An intact plaque can be seen on a plaque located in Harpers Ferry.)

The Return of Wheelspur Yard

During the 1960s, another rail tunnel under the East River was proposed; it was eventually decided to build it at 63th Street and work began in 1969 on what would carry both subway (MTA) and commuter (LIRR) trains; the LIRR would then connect directly with Grand Central Station. Like other tunnel projects in New York City, work progressed slowly and costs continually rose. Construction was cancelled entirely in 1976, though a subway connection to Long Island City was later finished, opening in 1989. In 2007, work began on the East Side Access project which would complete the LIRR connection to Grand Central–it may be completed by 2023. The project has already had an impact on Long Island City, though (beyond the large construction area). Much of the land that was once Wheelspur Yard had been built upon in the years since its demise and housed various commercial tenants. Between 2010 and 2012, many of those tenants were evicted or otherwise forced out–the MTA had plans for the land. The East Side Access project had taken over most of the nearby Arch Street Yard, which LIRR’s freight tenant the New York and Atlantic had previously used. So, the MTA planned to rebuild Wheelspur Yard for the NY&A. Before all the buildings had vacated, however, Hurricane Sandy hit. On October 29, 2012, much of the low-lying former marshland was inundated with up to six feet of water. Remaining tenants suffered severe damage. The flood was followed by a fire in another building weeks later. The buildings were slated for destruction regardless, and those not destroyed by fire were demolished soon after.

In early April, 2015, freight cars began to return to Wheelspur Yard for the first time since the late 1950s. In June, Mitch Waxman noted on the Newtown Pentacle that the increased railroad activity meant that the drawbridges spanning Dutch Kills would likely be replaced. He says of the Dutch Kills Swing:

It’s not long for this world, as the LIRR and MTA are rekajiggering a bunch of their operations in LIC at the moment. The Wheelspur Yard actually has freight rail running through it again, for instance, and there’s been a lot of chatter about plans for the relict Montauk Cutoff tracks which has reached me recently. [3]

Just what the future holds for the Dutch Kills Swing Bridge remains uncertain. For now its rusting presence is a reminder of a time when the Dutch Kills and Newtown Creek were vital waterways and the railroads ruled over Long Island City.