Crosses: Rockaway Inlet in Jamaica Bay

Connects: Floyd Bennett Field, Brooklyn and the Rockaways, Queens, NY [satellite map]

Carries: 4 vehicular lanes, 1 pedestrian sidewalk

Design: vertical lift bridge

Date opened: July 3, 1937

Postcard view: “Marine Parkway Bridge, Brooklyn, N.Y.”

The Marine Parkway Bridge (also known as the Marine Parkway-Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge) is a vertical lift bridge which connects Flatbush Avenue at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn with Jacob Riis Park and Fort Tilden in the Rockways in Queens.

Plans for a New Bridge: Robert Moses & The Marine Parkway Authority

Fiorello LaGuardia was narrowly elected Mayor of New York City in 1933; he would serve three terms from 1934 to 1945. LaGuardia was impressed by the parkways Robert Moses had built in Long Island (and by his ability to raise federal funds to finance them), and he immediately offered him a job in his administration. Moses had plans for parkways and parks in New York City ready to go, and he only agreed to take the job from LaGuardia if he would have control of the parks departments in all five boroughs, which had previously been independent of one another. Moses also wanted control of the parkways; LaGuardia agreed. Moses quickly took over the the Triborough Bridge Authority; that bridge’s construction had begun in 1929 but had stalled and remained incomplete. He also introduced a plan to finance construction of the Marine Parkway Bridge that called for the creation of the Marine Parkway Authority, of which, of course, Moses would be chairman and sole member. He raised money for these and other projects (which would charge tolls when they opened) by issuing bonds; when a project was complete, he would not sell off the bonds but would begin another toll-collecting project, continuing the cycle.

Opposition

Moses issued $6,000,000 in bonds in order to build the Marine Parkway Bridge, and it was expected that within 25 years, through toll collection the bridge would pay for the loan and allow the bridge to be self-sustaining. However, there was plenty of opposition to the bridge proposal. The surrounding communities had been served by ferries and many people did not want to see that change. There were others who felt that Jamaica Bay might one day become a major port and the building of a bridge would destroy that potential. So, more than $18 million was spent by the U.S. War Department to dredge Rockaway Inlet and the bridge was designed to be a lift span, to enable the channel to remain clear for ship traffic. There was also the issue of ice: it was feared that ice would pile up on the bridge piers and either block passage or cause the surrounding areas to flood, sweeping cottages along Rockaway Beach out to sea. The solution was to bring in a forest of 600-foot-tall Douglas fir trees from the west coast to be driven into the sand and act as fenders against the ice around the bridge’s piers.

The Barren Island Squatters

Another problem encountered before construction of the bridge could begin was a well-established colony of squatters living on what formerly was known as Barren Island. Barren Island was a roughly three mile long and one mile wide stretch in the southern Brooklyn section of Jamaica Bay. In the late 1800s, the land at either end of the island the island was home to several putrid-smelling industries including fish, fat, and offal rendering plants and another that rendered horse bones into glue, leading to the the body of water on the island’s western shore’s name: Dead Horse Bay. About 120 acres in the center of the island was owned by the city, intended to be used as a dumping ground. However, due to the city’s neglect, the land was taken over by a colony of squatters, who by 1877 numbered around 100. The squatters kept livestock such as goats and pigs, and even set up a liquor saloon on the island. The stench of the rendering plants grew worse and worse, and after years of complaints from Brooklyn residents, the plants were required to dump their refuse at sea. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle described the situation in 1899 as being “improved:”

Nowadays the ancient cheeses, the butchers’ offal, the long-deceased animals, the contents of refuse cans and barrels are not piled along the waterfront… On the contrary, the process is quick and thorough. Deodorizing substances are freely used in the materials that are disgorged from New York’s thousands of kitchens and butcher shops. The sufferings that are reported in various parts of Brooklyn and along the south shore probably result in larger measure than the people realize from the dumping which is still carried on at sea, the scows going out six or eight miles, instead of the required forty, and throwing overboard tons of swill that the incoming tide washes upon the shored of Coney Island, Rockaway and even Long Beach. This vile stuff festers in the sun, sours and breeds maggots and flies by millions. [1]

Despite many attempts over the years to remove the squatters, they stayed put. Barren Island was connected to the Brooklyn mainland with landfill during the construction of Floyd Bennett Field (New York City’s first municipal airport), which opened in 1931. By then the rendering plants were long gone, but the squatters still remained. In 1936, Robert Moses, as Park Commissioner, called for their eviction; at that time there were an estimated 90 squatters (and their livestock) still living on the former island. They were given until April 15, 1936 to vacate, and Alderman Joseph B. Whitty of Brooklyn was granted a promise by Mayor LaGuardia that the houses on the island would be treated as “condemned tenements” [2], so that the squatters would be provided with free moving service as they left the island. In August of the same year, five acres of marijuana plants were discovered on the island, upon which the goats the squatters had kept had been grazing. The squatters, when questioned, denied that there was any other intended use for the plants.

Engineering

Moses the planner had engineers ready to work on the Marine Parkway Bridge. The chief engineer on the project was Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute graduate Emil H. Praeger (who worked on numerous projects for the Parks system and went on to design the Tappan Zee Bridge). The firm of Madigan-Hyland were also involved as engineers. Robinson & Steinman were hired as consultants; Holton D. Robinson was the engineer of the Williamsburg Bridge and David Steinman designed the Henry Hudson Bridge as his thesis while at Columbia University. The title of Engineering Designer was filled by the esteemed Waddell & Hardesty, formed in 1927. Also both Rensselaer graduates, the firm of J.A.L. Waddell and Shortridge Hardesty was known for its movable bridge designs, especially vertical lift spans. The contractors awarded the bids for construction of the bridge were the Frederic Snare Corporation and the American Bridge Company.

Construction & Design

Construction began on June 1, 1936. A method differing from usual lift bridge construction was used, where instead of floating the lift span in at the very end, it was placed partway through, planned to coincide with a particularly high tide. Just after midnight on January 12, 1937, 38 workmen from the American Bridge Company began the operation; tugboats guided the central span along and at 7:45 a.m., while the tide was at its highest, it was placed into position. The partially built towers had a special trestle attached to their foundations from which the towers would be completed.

The bridge is designed of three main 540-foot spans, each allowing for a 500-foot clear channel. There are two 1,061-foot approaches; its total length is 4,022 feet, 6 inches. The 2,000-ton central span could be raised from 50 feet to a total clearance of 150 feet above the high water mark in two minutes. When it was completed it was the longest highway lift bridge in the world (it is still the longest of its type in North America), built of 12,000 tons of steel and 47,000 cubic yards of concrete. The bridge was painted olive green with silver trim. The roadway, instead of being solid, was built of steel plates, similar to subway gratings set in sidewalks throughout the city. It was the first roadway of this type to be used on a bridge on the East Coast. The open grates were also painted green.

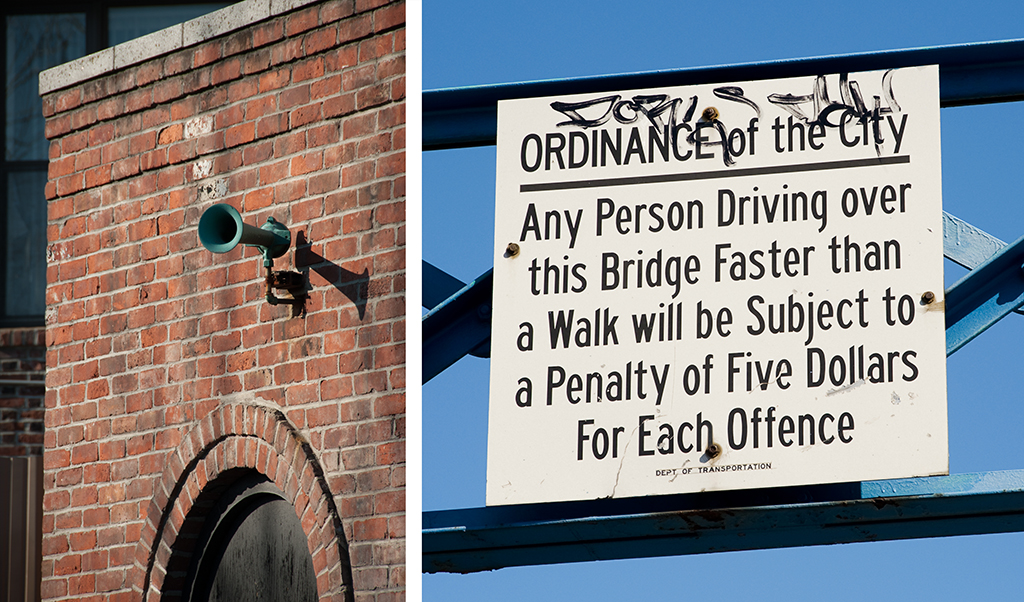

One complaint about vertical lift bridges at the time was that their appearance could be ugly; often they were employed by railroads and were decidedly utilitarian in design. In response to this, the towers of the Marine Parkway Bridge were tapered and a pattern designed to hint at the great wheels that lifted the bridge rather than hiding them [3]. Construction was finished less than a year after it began, and the bridge was scheduled to open in July, in time for motorists to enjoy the summer in the new Jacob Riis Park.

Opening Ceremony

The bridge officially opened on July 3, 1937. The ceremony was headed by Mayor LaGuardia who was joined by Park Commissioner Robert Moses and various other city officials. 500 cars full of invited guests waited on the Brooklyn side of the bridge, on the approach built on Barren Island. Guns were fired from Fort Tilden, fireboats sprayed water into the air, and nine Martin planes flew in formation overhead. The center span was lowered for traffic and at 10:30 a.m. a parade of cars began to cross the bridge to Jacob Riis Park, where Moses gave a speech detailing the planning that had led up to the building of the bridge. It was given recognition in the engineering world as well: The National Steel Bridge Alliance awarded it first place in the movable bridge category in 1937.

Renaming & Rehabilitation

The bridge was renamed in 1978 in honor of Gil Hodges, a former Brooklyn Dodgers first baseman, though the name has not taken into common usage [4]. The Marine Parkway Authority was absorbed into the larger Triborough Bridge Authority in 1940 (becoming he Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority in 1946). Traffic and toll collection on the Marine Parkway Bridge did not turn out to be enough to pay for its own expenses, but other bridges and tunnels run by the TBTA were profitable enough to carry those that were less so. The TBTA is now under the jurisdiction of the MTA, who began a major rehabilitation project on the bridge in 1998. The steel deck was replaced with concrete and steel, a “Jersey” barrier was added to separate traffic, electrical systems and traffic control were updated, and new signs were put in place. The $120 million project was finished in 2004; the bridge still opens more than 100 times a year.