Crossed: Newark Bay

Connected: Elizabeth and Bayonne, NJ [satellite map]

Carried: 4 railroad tracks (Central Railroad of New Jersey)

Design: Vertical lift bridge

Date opened: November 27, 1926

Date demolished: 1980-1988

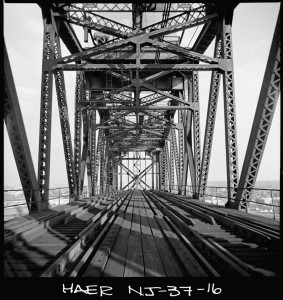

The Central Railroad of New Jersey Newark Bay Bridge was a two-mile-long vertical lift bridge which consisted of two spans that each carried two railroad tracks. The bridge crossed two shipping channels in Newark Bay and therefore had two lift spans, each with two draws that could be moved independently. The bridge carried both passenger and freight trains.

Previous Bridges

The Central Railroad of New Jersey, also known as the Jersey Central (and often shortened to CNJ), was a railroad that had its beginnings in the 1830s. Originally called the Elizabethtown and Somerville Railroad, it connected Elizabethport and Elizabeth, NJ in 1831 before extending outward to Somerville in 1842. It was renamed the Central Railroad Company of New Jersey in 1849, as it continued its expansion by building new track and acquiring other railroads; by 1852 it reached Phillipsburg, on the Delaware River. The first bridge built by the CNJ across Newark Bay was a wooden trestle with a steel swing span that opened on a central pier. It carried two tracks and opened in 1864; this line ended at the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal, located on the Hudson River waterfront in what is now Liberty State Park in Jersey City (the original 1864 building was replaced in 1889 with the Romanesque structure which still stands).

In 1903, work was begun on a replacement for the wooden bridge. Maritime traffic had increased steadily, and the volume and size of the trains crossing the bridge had also grown. The swing span had to open frequently and the CNJ also wanted to plan for an expansion of the crossing from two tracks to four. The design selected consisted of two Scherzer Rolling Lift spans; a key advantage over the swing bridge was that the bridge would not need to open fully to allow passage of barges and other low ships. The two-track sections could be expanded to four by building an additional span with identical Scherzer Rolling Lifts next to the existing spans. The west leaf of the movable span was floated into place on February 14, 1904 [1] and followed by the east leaf a few months later. The new span was seen as a vast improvement over the wooden trestle.

From Newark Meadows to Port Newark

However, the character of Newark Bay continued to change. The city of Newark began dredging the shallow Newark Meadows during the 1910s to create an additional shipping channel, which later became Port Newark (it is now known as the Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal). During World War I the U.S. government used Port Newark to station troops. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey was formed in 1921 and was followed by the Rivers and Harbors Acts of 1922, which authorized the creation of even more shipping channels. As the crossing closest to the new facilities and the longest crossing, the bridge came to be seen as a huge obstruction to the growing port [2]. Authorities in Newark were in favor of demolishing the bridge altogether and replacing it with a tunnel (which wouldn’t obstruct marine traffic at all). Cost was an issue; a tunnel was estimated at $100 million whereas a replacement bridge would cost $9 million. Proposed by the CNJ in 1922, the replacement bridge, of a vertical lift design, would have two spans (200 feet and 125 feet wide) that would raise for a maximum clearance of 135 feet above the water; they would replace the Scherzer spans which were 85 feet wide each. U.S. Secretary of War John W. Weeks decided in favor of a vertical lift bridge in December of 1922 [3]. However, that was not the end of opposition to the bridge. In November, 1924 a case was brought to the Supreme Court against the CNJ by the state of New Jersey (led by Newark and Jersey City), questioning the right of a railroad to build across a state’s navigable waters [4]. On March 2, 1925 the Supreme Court decided in favor of the railroad [5] and plans to replace the bridge moved forward.

Vertical Lift Bridge

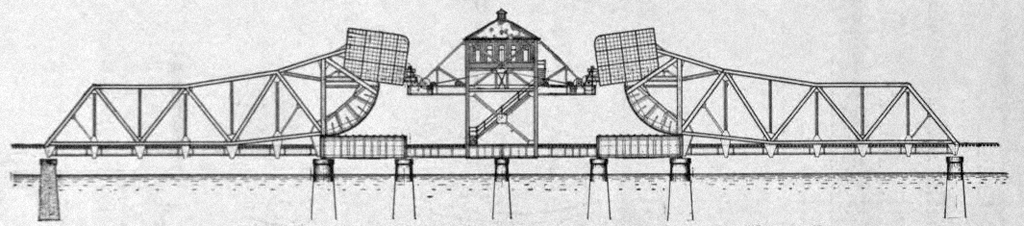

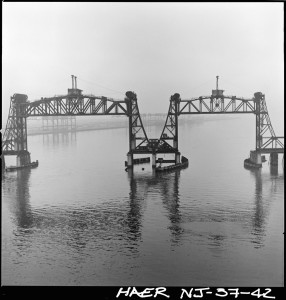

The Central Railroad of New Jersey sped construction of the new bridge as soon as approval had been granted. The bridge’s designer was John Alexander Low Waddell, a civil engineer well known for his vertical lift bridges. Waddell had moved to New York City in 1920 and was towards the end of a bridge-building career that had begun with a lift bridge in Chicago in 1892-3. The bridge was “believed to be the world’s longest drawbridge” [6]; the bridge’s Chief Engineer Arthur E. Owen declared it to be “the largest drawbridge assembly in the world” [7]. While neither claim was ever definitively proven, it would be hard to argue that the bridge was not impressive. The new spans carried four tracks over Newark Bay; the two shipping channels were crossed by double vertical lift spans that each operated separately from one another. The main difference in the functionality of the new bridge was that its height in the closed position was a minimum of 35 feet above the water, so while the Scherzer Rolling Lift improved upon the previous swing in that it only had to open partially for barges, the new bridge spans only had to open at all for taller ships (allowing the passage of many vessels at all times).

The new Central Railroad of New Jersey Newark Bay Bridge was formally opened on November 27, 1926. It had cost roughly $14 million (far higher than the original $9 million estimate several years earlier). The inaugural train riders included twenty-two “veteran” commuters of the line, most notably a resident of Elizabeth named K.S. Kiggins, who had also attended the first bridge opening in 1864 [8]. New Jersey governor Harry A. Moore, several New Jersey mayors, CNJ president Roy B. White, and many holding high positions at various other railroads were also in attendance. In 1927, W.C. Hope, the passenger traffic manager of the CNJ, released statistics stating the the new bridge had allowed 60% of all marine traffic to pass below it without opening, a steep decline in openings compared to the older bridge [9].

Tragedy

At 10am on September 15, 1958, a CNJ commuter train heading towards Bayonne from Bay Head plunged off the south span, which was partially lifted, and into Newark Bay. The train had proceeded past three stop signals; evidence of mechanical failure was never found and it was believed that the engineer had suffered a heart attack. After a dramatic rescue and recovery effort over the next several days, it was declared that 48 people had died in the tragedy–45 passengers and three crew members. Notable among the dead were former second baseman for the Yankees George (Snuffy) Stirnweiss and John Hawkins, the mayor of Shrewsbury, NJ. Later in 1958, the CNJ announced it would be adding new safety measures: automatic trippers would bring rogue trains to a stop if they ignored stop signals (by using a derail system), and “dead-man” controls would stop trains if the operator released the throttle [10].

Abandonment and Demolition

The bridge was in for more trouble, however. On a very foggy May 19, 1966, the French freighter S.S. Washington hit the northeast vertical lift span, rendering the two tracks it carried unusable. Furthermore, he overall decline of the railroads was taking its toll on the CNJ; overall ridership was down and in May 1967 the Aldene Plan went into effect. It rerouted CNJ trains departing from Aldene (in Roselle Park, NJ) to Newark rather than over the Newark Bay Bridge. This meant that the only passenger service over the bridge was a shuttle running from Bayonne to Cranford; nicknamed the “Scoot,” its service was very limited. In light of these changes, the damaged span was never repaired.

Use of the bridge continued its steady decline. By the 1970s, CNJ had moved the rest of their freight operation to Elizabeth and only two freight trains a day crossed the span.The Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) took over the operations of the Central Railroad of New Jersey on April 1, 1976 and moved all freight operations to the Pennsylvania Railroad Newark Bay Bridge, north of the CNJ span. The last passenger train crossed the bridge was on August 6, 1978.

The abandoned bridge was deemed a hazard to navigation and an attempt was made to save the bridge by the City of Bayonne. The city was unsuccessful, and on July 11, 1980 explosives were used to partially demolish the bridge. The vertical lift spans and towers fell, engulfed in smoke. The approaches and remaining trestles were removed in 1987-1988, leaving only portions of the piers along the shorelines as visual reminders of the structure that once crossed the bay. The Bayonne Historical Society held a memorial for victims of the commuter train crash in 2008, 50 years after the accident, but other than that the bridge has been largely forgotten. Some remaining portions of the bridge were blasted away as recently as February, 2012 [11]. On the Bayonne waterfront, cormorants and seagulls can be seen roosting on the few crumbling piers that still extend into Newark Bay today.