Location: Hunters Point Avenue over Dutch Kills, Queens, NY [satellite map]

Carries: 2 vehicular lanes, 2 pedestrian sidewalks

Design: bascule

Date opened: December 14, 1910

The Hunters Point Avenue Bridge carries the street bearing its name across Dutch Kills, a tributary of Newtown Creek, in Long Island City, Queens.

The Need for Movable Bridges

The section of Queens now known as Long Island City was originally low-lying marshland dotted with small towns. In 1861 the Long Island Railroad arrived after relocating its main terminal from Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn to Hunters Point in Queens (a ferry leaving 34th Street carried passengers across the East River to Hunters Point). With the area rapidly industrializing, in 1869 Hunters Point pushed to to be incorporated into a larger, more important entity, combining with Ravenswood and Astoria. Thus, in 1870 Long Island City was born. Industry boomed, and gas and chemical plants along with various other types of factories took over much of the marshland. Of course, no regulations existed at the time to dissuade the dumping of toxic by-products into the waterways, and Newtown Creek and Dutch Kills both suffered sorely from this industrial pollution. Both rivers were heavily used and required bridges that allowed the waterways to remain navigable, so a large concentration of movable bridges is seen in the area.

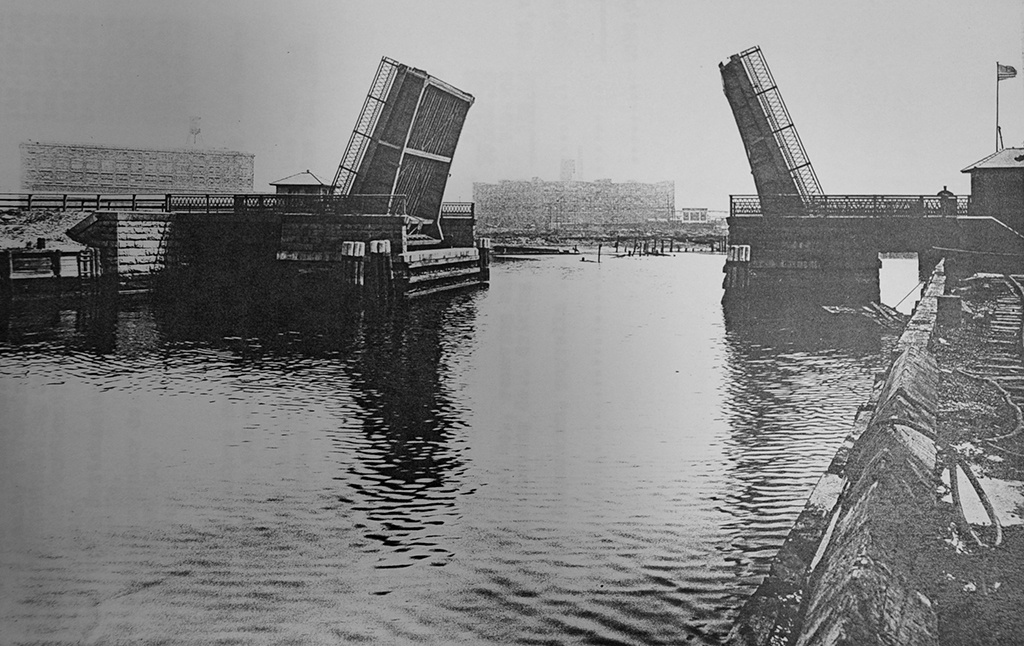

Previous Bridges

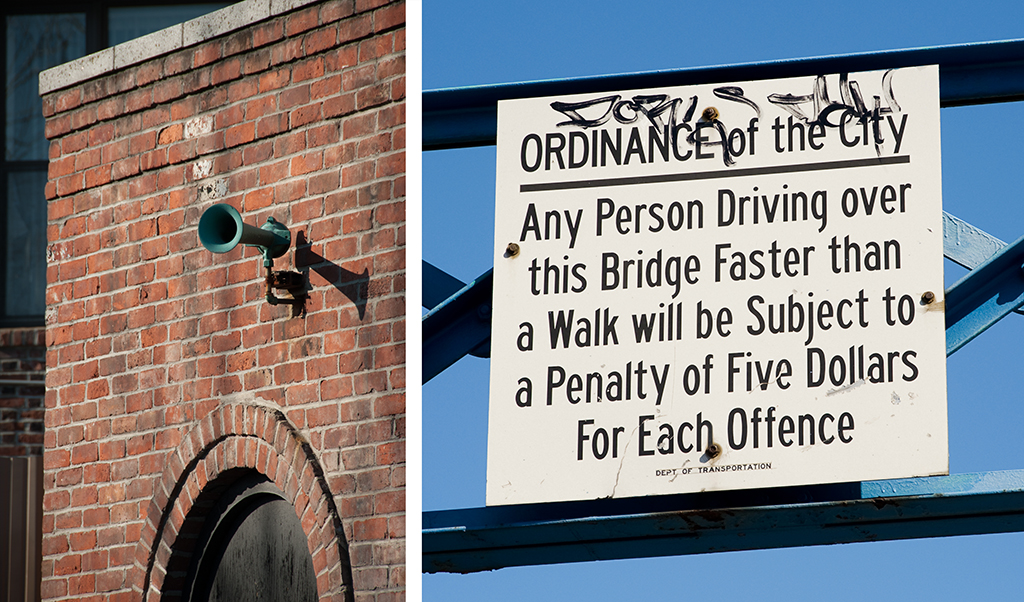

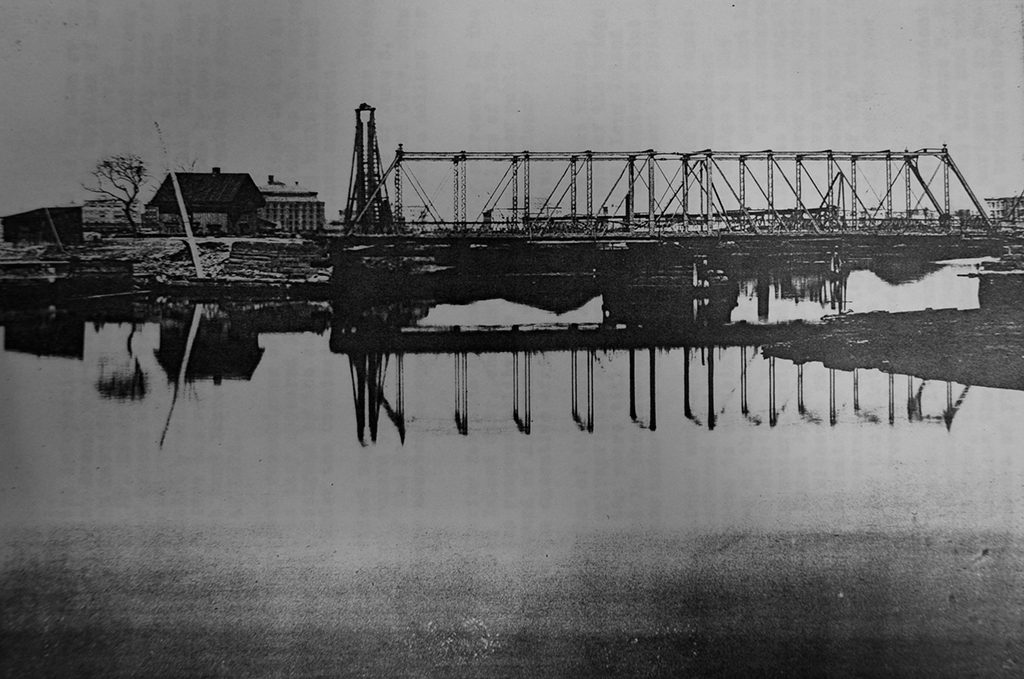

Prior to 1874, Dutch Kills was crossed at Hunters Point Avenue by a wooden bridge. With so much industry moving in to the area, it was soon inadequate and was replaced in 1874 by an iron drawbridge. The iron drawbridge was problematic, and frequently had to be put out of service to be repaired. The bridge was poorly maintained and it was obvious something had to be done to keep navigation on Dutch Kills open. In 1906, Bridge Commissioner James W. Stevenson wrote to Queens Borough President Joseph Bermel requesting that since the bridge was over navigable water it ought be operated by the Department of Bridges. Bermel agreed, and on January 25, 1906, the bridge was put under the jurisdiction of the Department of Bridges, having just been put back into working order by the Department of Highways. By March 1907, it was found that the west abutment had been pushed forward by the ever-shifting marshland and the bridge could no longer close. The iron bridge was closed to traffic permanently and the Department of Bridges began planning for its replacement.

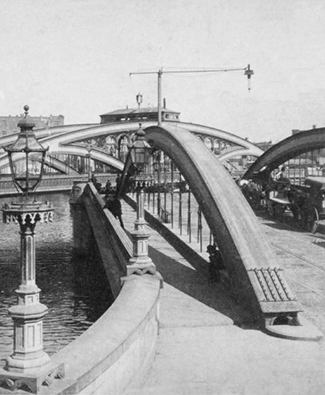

The Scherzer Rolling Lift Bridge

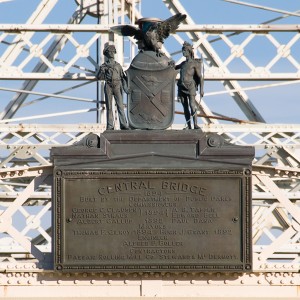

The design approved by the Art Commission on April 13, 1909 was for a double-leaf Scherzer Rolling Lift bascule bridge. Bids were received in July; the North-Eastern Construction Company was the lowest at $95,214.11 and was given the contract to build the bridge. Construction began on July 13, 1909 and the bridge opened to traffic on December 14, 1910. The final cost was $102.985.56, about $8000 over the bid but still under the $110,000 budget allotted to it by the Department of Bridges.

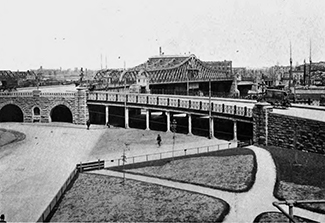

Rebuilding

By the 1970s, following decades of neglect, many of New York City’s bridges were in need of major rehabilitation. The Department of Transportation released its first-ever survey of bridge conditions in 1978 and the Hunters Point Avenue Bridge was included on the “poor” list. This was for good reason: the previous year it had been closed entirely because parts of it had rotted away, rendering it unsafe for traffic. It was repaired just enough to handle cars, but a major rehabilitation was needed. In 1983 it was rebuilt as a single-leaf bascule bridge with a span of 21.8 meters, using the foundations of the Scherzer bridge. It celebrated its 100th birthday in December 2010, which was marked by a walking tour hosted by the New York City Bridge Centennial Commission and the Newtown Creek Alliance.