Location: Bronx River north of the Westchester Avenue Bridge, Bronx, NY [satellite map]

Carries: 3 railroad tracks (Amtrak and CSX)

Design: Scherzer Rolling Lift (bascule)

Date opened: summer 1908

The name “Bronx River Bascules” is not an official one. In fact, these bridges do not seem to have ever been given a proper name. The New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, which constructed them, referred to them simply as “bridge number 3.40” [1]. They cross the Bronx River just north of Westchester Avenue and were put into service in the summer of 1908.

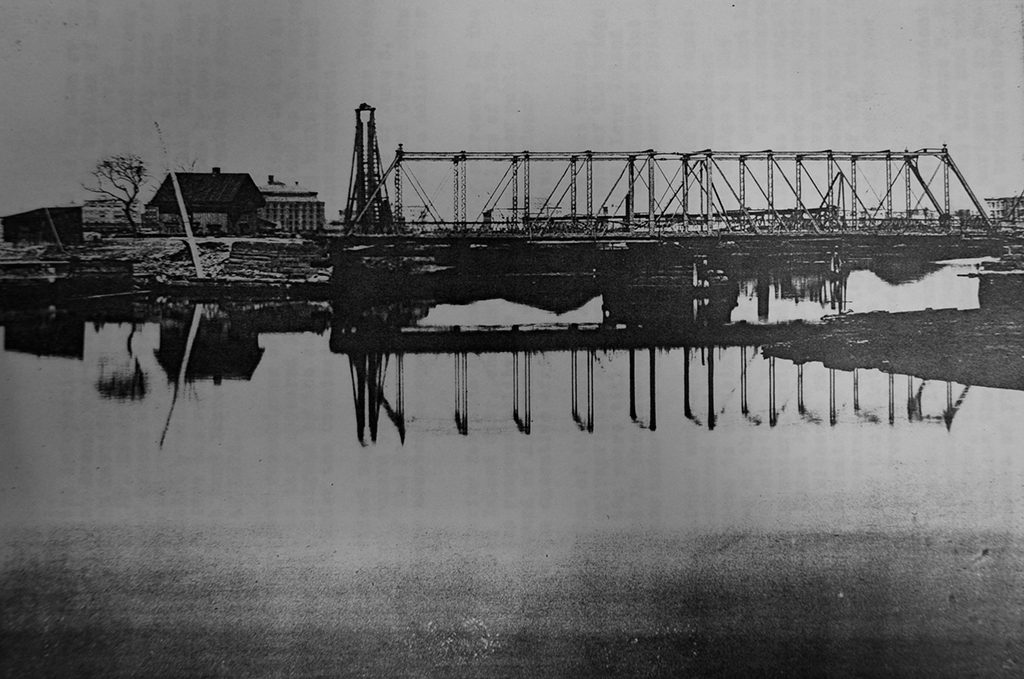

The Harlem River Branch

The New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad began running passenger and freight service on their Harlem River Branch in 1868. Two jackknife drawbridges carried trains over the Bronx River at the present site until 1893, when they were replaced by a four-track swing bridge. In 1907, the swing was removed and two temporary jackknife drawbridges were put in place. Between 1908 and 1910 the Harlem River Branch was completely rebuilt to carry six tracks and run on electricity. New stations were also built along the route. The closest was the Westchester Avenue station, which stands in ruins today to the south of the bridges, local passenger service having been discontinued in the 1930s.

Construction

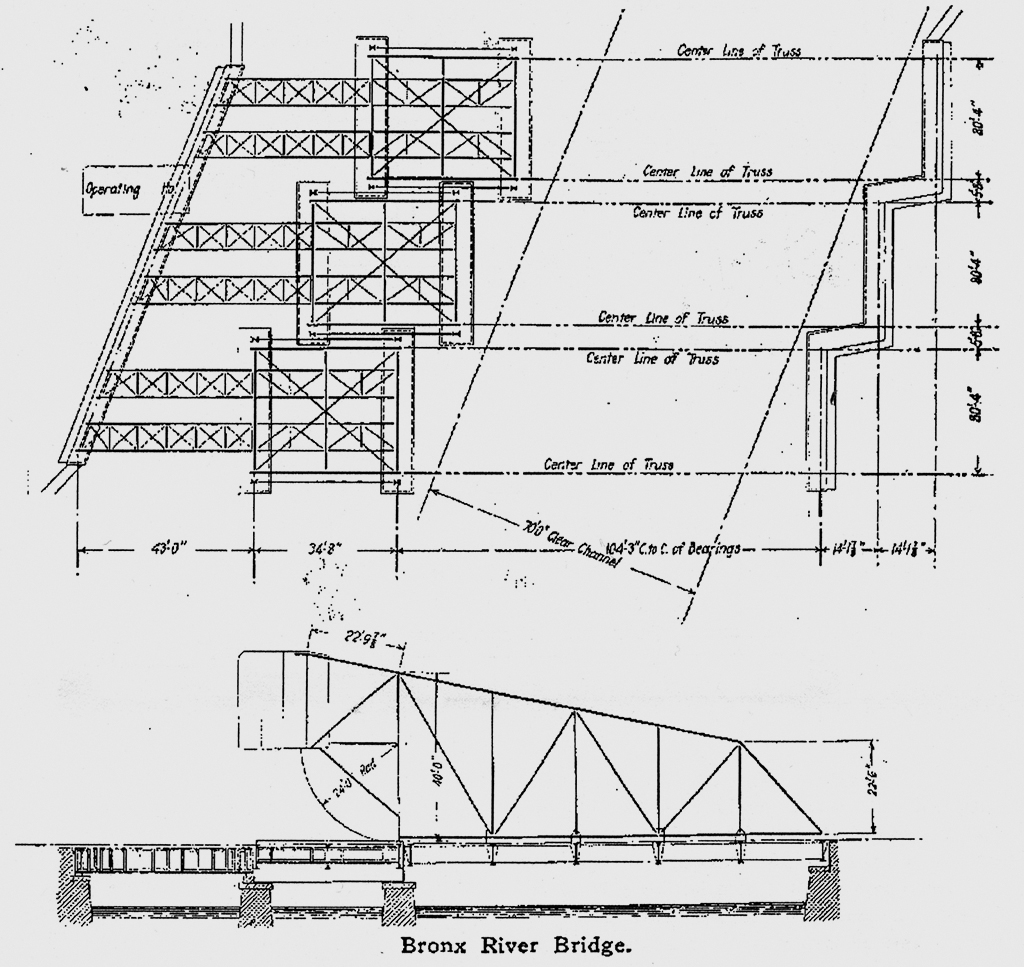

The bridge superstructure, as originally built by the Pennsylvania Steel Company, was made up of three parallel two-track spans with separate piers on each end, staggered to accommodate the curve of the Bronx River (see diagram). Since the channel is so narrow (about 100 feet wide), the type of bridge chosen was a bascule, which did not obstruct the waterway as the swing bridge had. The particular type of bascule is the Scherzer Rolling Lift, invented by William Scherzer in Chicago; they operate by rolling back into the open position, rather than turning on a fixed axle as in other bascule designs. Since the Harlem River Branch was being electrified, tall towers were put up to carry high voltage wires above the bridges while in the open possition. Each leaf of the bridge was powered by two Westinghouse 25 horsepower, 550 volt direct current motors. All three leaves could be raised simultaneously in about a minute, and as a backup could be opened manually with a chain, though it was never necessary to do so.

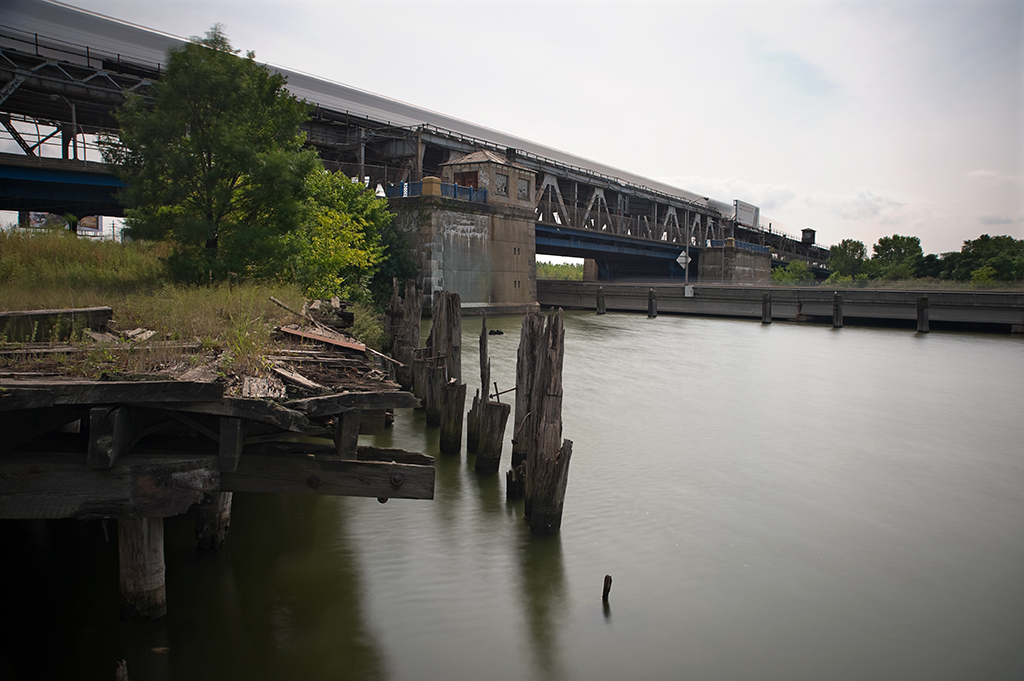

Growth & Decline

About 200 trains passed over the bridges daily during their first years of operation; on average they opened 5 times a day during the winter and 12 times a day throughout the rest of the year [2]. With the opening of the Hell Gate Bridge by the New York Connecting Railroad in 1917, the Harlem River Branch became part of a much larger through route accommodating trains traveling from Penn Station to Boston. Over the years rail service declined, as did use of the Bronx River by boats requiring bridge lifts for passage. At some point, the tower containing the operating machinery and one two-track span were removed. The bridges now have only three tracks: one used by CSX for freight and two carrying Amtrak passenger trains on the Northeast Corridor Line.